This afternoon Mike and I sat upstairs on the deck at our place, looking out towards the trees. It was pouring rain. Water was sheeting off the tin roofs of the houses behind us and running down the big green leaves of the coconut trees – arcing off and dropping towards earth in one, unbroken, stream.

This afternoon Mike and I sat upstairs on the deck at our place, looking out towards the trees. It was pouring rain. Water was sheeting off the tin roofs of the houses behind us and running down the big green leaves of the coconut trees – arcing off and dropping towards earth in one, unbroken, stream.

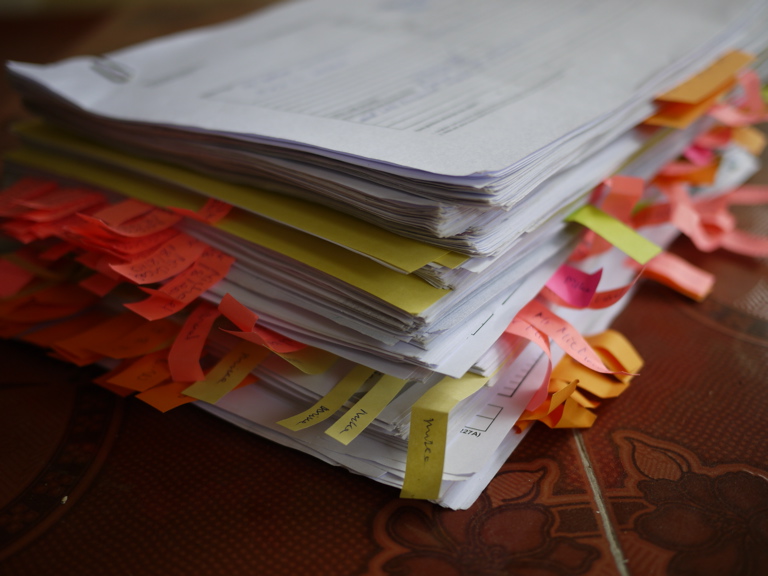

We were up there because Mike had quit the kitchen table, which was burdened by our two laptops and a stack of documents eight inches thick that he’d bought home to sign over the weekend. The stack was peppered with neon tags demanding his signature.

“Mr Michael,” the tags read, one after another.

Mr Michael. Mr Michael. Mr Michael…

On this quiet Sunday afternoon Mr Michael had worked through all these documents, not pausing until near the end, when he came across three requests for reimbursement. These were all related to cases where a sponsor child had gotten sick out in their village and the district health centers hadn’t been able to address their problems and had recommended transfer to the provincial health center in Luang Prabang.

It costs money to transfer sick children to the provincial hospital, and when three children get critically ill in one district within a month, it costs more money than has been budgeted for medical emergencies. Significantly more. As in, more than half the budget for the entire year.

“It’s not three cases,” Mike reminded me, when I went to see where he’d gone and found him sitting at the table on our deck, staring out at the rain. “It’s four. We also have little orphan girl.”

Ah, yes. Little orphan girl. Little orphan girl whose story began two weeks ago now, when Mr Michael received multiple phone calls on a Saturday requesting him to authorize the medical transfer of an eleven-year-old child from Luang Prabang to Vientiane. The doctors in Luang Prabang said they couldn’t treat her here, that she had a problem in her brain and that she would probably die if not flown to Vientiane for specialized medical care immediately.

Mr Michael authorized the medivac. At first, it seems, the doctors in Vientiane thought she had Japanese encephalitis – she could not even sit up, or swallow – but after a week of testing these results came back clear. So she does not have encephalitis, but no one is any the wiser yet on what she may have.

At least, this is what we think is going on. It’s very difficult to get accurate information. Whatever the doctors in Vientiane are saying gets filtered through at least two other Lao speaking staff before it reaches the office up here. To complicate matters further, little orphan girl herself doesn’t speak Lao, much less English. Little orphan girl is an ethnic minority child who is too poor to attend school, where she would learn Lao. So she only speaks Khmu, and the doctors only speak Lao.

I was speaking about this with the local staff member on the case during our house-warming party on Friday night.

“So, no one knows what is wrong with her brain,” I said, trying to make sure we were on the same page. “But now she needs help to get her muscles working again?”

“Yes,” the Iokina replied. “But the doctors say the problem will happen again. They say she will die.”

“But they don’t know what the problem is?” I said.

In summary: No. They don’t know what the problem is. They don’t know when “it” might happen again. They don’t know when she might die – it’s just that Iokina seems pretty certain that she will, at some point, especially if we send her back to the village with her fourteen-year-old sister and elderly grandmother.

“Do you think she should go back to the village?” I asked.

“Yes,” Iokina said, shrugging a little in that helpless way that needed no translating.

“We tried,” Iokina was saying, without words, “and there’s only so much you can do for one child.”

So Mike and I are left wondering. Is that really what the doctors have said? How do you weigh and filter this information that has come up to us across many miles and two significant language barriers? Would physiotherapy help her, or is the primary problem neurological? Are there any Khmu speaking physiotherapists in Luang Prabang that could coach her on exercises she could do at home? If so, how could we find them? How are her sister and her grandmother going to be able to help her when they need to be tending the rice fields so they can all eat? And, of course, how much is this all going to cost?

How do you put a price on the life of a child?

“The emergency medical fund is for emergencies,” Mike said today as we sat on the porch watching the rain. “This case is no longer an emergency. We don’t have the capacity to take on long-term rehabilitation cases. We cannot continue to pay for her treatment indefinitely when no one yet knows what may be wrong with her. She has to come back from Vientiane.”

“What then?” I asked.

“I don’t know,” Mike said. “I have to go in to the office early tomorrow before we head out to the field. I’ll see if I can get some more information.”

We sat and stared at the rain for a little while longer, and then we came inside and went back to work.

11 comments

Have you read “When the Spirit Catches You and you Fall Down”? It’s a GREAT book that I think you would enjoy. All about cultural and language barriers in medicine/treatment.

What a tough spot for Mike to be in . . . sending good vibes to you both.

Jos, funnily enough I did read that book just a couple of months ago – Leah recommended it when we were visiting her in Alaska. It was a brilliant book, wasn’t it? We gave Leah’s copy back, but it’s on my list of books to buy to have in my library.

What can we do to help her? Is there somewhere we can send money to help her case?

Thank you so much for your interest in ways to help. This is a bit of a tough issue that Mike and I continue to think on and discuss. There is no official way that people can donate specifically to help this little girl.

As for unofficially – good friends of ours in the States actually gave Mike and I some money to use as a mike&lisa emergency fund before we arrived in Laos. Their hope was that having a bit of a slush fund of our own may help ease the pressure of dilemma’s exactly like this one. And it has, a little, I must say. Although it’s also very difficult sometimes to judge how and when we could use that money without further complicating an already complicated situation.

Several times in the past two months we’ve been in situations where we thought “maybe this is a good use of the mike&lisa fund”. This story is one of those. I suspect that we will use a portion of this mike&lisa fund to help this little one. At the very least we intend to pay the $37.00 that her sister and grandmother borrowed from the village development fund to pay for initial medical treatment. The only way they can pay back that loan is to sell rice, and this family doesn’t have enough rice to start off with. I will stay alert to other ways we may be able to support her.

So, no pressure at all. Really. But if you would like to stay up to date on this story, send me an email on [email protected] and I will let you know if opportunities open for additional support for little orphan girl through unofficial or official channels.

Many thanks again,

lisa

[…] Wandering. Wondering. Writing. Lisa in Laos Skip to content Home ← What price a child’s life? […]

[…] also have an update (quite a good one) on little orphan girl that I’ll try and write up […]

[…] [Next time, in Part IV of this story, Money, it’s complicated, we revisit little orphan girl] […]

[…] It was about a month after we returned from Viengkham that Mike received his first phone call about the case of Lahela, little orphan girl. You can read the start of this story in the post titled: What price a child’s life? […]

[…] Hard choices in humanitarian work: What Price a Child’s Life? […]

[…] a humanitarian-work week on the blog. I’m going to tell you the next installment in the story of little orphan girl, and talk about how difficult it can be to spend money to help others in ways that do no harm. […]

[…] office. Get out of car. Pick up necessary visa forms from national office and discuss case of little orphan girl with relevant staff for five minutes. Get in car. Drive to the border. Get out of car. Get in line […]

Comments are closed.